Works of Art in the Cathedral Precinct

The Nave

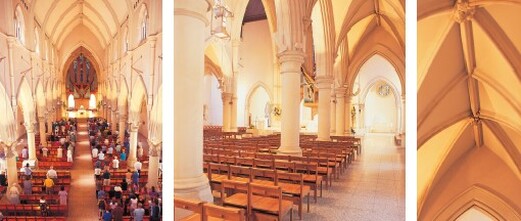

On entering the cathedral, the eye is drawn up at once to appreciate the full height and width of the cathedral. The quality of light in the cathedral is especially significant.

The lighting, which picks up gothic forms in its contemporary design, not only adds sparkle to the cathedral but sets the arches and vaulting in relief, emphasising the space in the nave and aisles. The lighting can be adapted to a wide range of occasions.

The cathedral chairs, each crafted from Queensland sycamore and equipped with a kneeler, show respect for the individuality of each person without compromising the sense of community which traditional pews were often able to achieve.

They provide a seating system which is neat and flexible. Provision can easily be made for someone in a wheelchair to sit with their family or friends, and other seating arrangements are possible for special occasions.

On entering the cathedral, the eye is drawn up at once to appreciate the full height and width of the cathedral. The quality of light in the cathedral is especially significant.

The lighting, which picks up gothic forms in its contemporary design, not only adds sparkle to the cathedral but sets the arches and vaulting in relief, emphasising the space in the nave and aisles. The lighting can be adapted to a wide range of occasions.

The cathedral chairs, each crafted from Queensland sycamore and equipped with a kneeler, show respect for the individuality of each person without compromising the sense of community which traditional pews were often able to achieve.

They provide a seating system which is neat and flexible. Provision can easily be made for someone in a wheelchair to sit with their family or friends, and other seating arrangements are possible for special occasions.

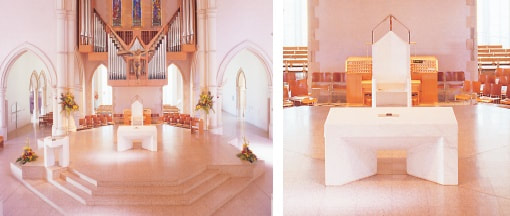

The Sanctuary

The sanctuary in the midst of the assembly is designed to give the sense of people gathered around the altar in a corporate act of worship. The action of the liturgy is not confined to the sanctuary: the whole cathedral is the place where worship is offered to God by the Church. The key elements in the sanctuary are the bishop’s chair (cathedra), ambo and altar. They were designed by architect, Robin Gibson, and crafted in Carrara marble by Peter Schipperheyn.

The Bishop’s Chair: The bishop’s chair echoes the simple form of ancient bishops’ seats from the early middle ages. It is surmounted with a steel frame which refers to the form of the bisho’s mitre and which evokes the presence of the bishop as chief pastor in his cathedral church.

The Ambo: Readings from scripture play an important part in the celebration of all the sacraments. Just as people are fed with the Lord’s body and blood from the table of the Eucharist, so too are they nourished on the Word of God proclaimed in the liturgical assembly. The ambo’s design and proportions emphasise its balanced relationship with the altar.

The Altar: The altar changed in shape in the middle ages when the priest began to celebrate the eucharist with his back to the people. It sometimes was reduced to a kind of shelf in a highly ornate wall or backdrop. It was elongated to allow for the reading of the epistle and gospel at either end. Today it is again free-standing and of a smaller, squarer shape. The altar, where the sacrifice of the cross is made present under sacramental signs, is also the table of the Lord. The people of God is called together to share in this table. The double aspect of altar and table is held together through the design of St Stephen’s altar and its change in texture.

The sanctuary in the midst of the assembly is designed to give the sense of people gathered around the altar in a corporate act of worship. The action of the liturgy is not confined to the sanctuary: the whole cathedral is the place where worship is offered to God by the Church. The key elements in the sanctuary are the bishop’s chair (cathedra), ambo and altar. They were designed by architect, Robin Gibson, and crafted in Carrara marble by Peter Schipperheyn.

The Bishop’s Chair: The bishop’s chair echoes the simple form of ancient bishops’ seats from the early middle ages. It is surmounted with a steel frame which refers to the form of the bisho’s mitre and which evokes the presence of the bishop as chief pastor in his cathedral church.

The Ambo: Readings from scripture play an important part in the celebration of all the sacraments. Just as people are fed with the Lord’s body and blood from the table of the Eucharist, so too are they nourished on the Word of God proclaimed in the liturgical assembly. The ambo’s design and proportions emphasise its balanced relationship with the altar.

The Altar: The altar changed in shape in the middle ages when the priest began to celebrate the eucharist with his back to the people. It sometimes was reduced to a kind of shelf in a highly ornate wall or backdrop. It was elongated to allow for the reading of the epistle and gospel at either end. Today it is again free-standing and of a smaller, squarer shape. The altar, where the sacrifice of the cross is made present under sacramental signs, is also the table of the Lord. The people of God is called together to share in this table. The double aspect of altar and table is held together through the design of St Stephen’s altar and its change in texture.

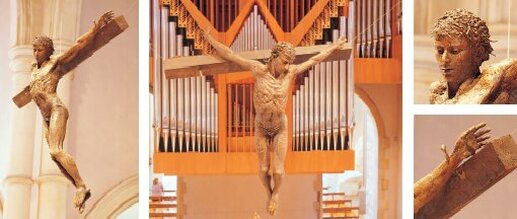

The Jubilee Pipe Organ

The Jubilee Pipe Organ was inaugurated on 28 October 2000 and blessed on 29 October. It is named after the Year of the Great Jubilee 2000Meticulously constructed by Victorian, Knud Smenge, to the design of architect Robin Gibson it incorporates 2442 pipes and weighs 16 tonnes. The organ has three manuals with 44 stops in four divisions, Great, Positiv, Swell and Pedal. The impressive case is made from imported mahogany and Victorian fiddleback mountain ash.

The tonal quality of the organ has been described as possessing a uniquely Australian character: bright and forthright, yet inherently gentle. The organ offers all the versatility the liturgy demands: loud enough to lead a thousand people in song, yet soft enough to provide accompaniment to a soloist. More>>

The Jubilee Pipe Organ was inaugurated on 28 October 2000 and blessed on 29 October. It is named after the Year of the Great Jubilee 2000Meticulously constructed by Victorian, Knud Smenge, to the design of architect Robin Gibson it incorporates 2442 pipes and weighs 16 tonnes. The organ has three manuals with 44 stops in four divisions, Great, Positiv, Swell and Pedal. The impressive case is made from imported mahogany and Victorian fiddleback mountain ash.

The tonal quality of the organ has been described as possessing a uniquely Australian character: bright and forthright, yet inherently gentle. The organ offers all the versatility the liturgy demands: loud enough to lead a thousand people in song, yet soft enough to provide accompaniment to a soloist. More>>

The Crucifix

Suspended over the sanctuary, the bronze crucifix is the work of John Elliott. It captures Jesus’ pain, suffering and death but also his strength, triumph and resurrection. In this way the crucifix seeks to express the whole of the Easter mystery. The cross can be viewed as a powerful sculpture not only from the front as most crucifixes are but also from the sides and from the rear.

Suspended over the sanctuary, the bronze crucifix is the work of John Elliott. It captures Jesus’ pain, suffering and death but also his strength, triumph and resurrection. In this way the crucifix seeks to express the whole of the Easter mystery. The cross can be viewed as a powerful sculpture not only from the front as most crucifixes are but also from the sides and from the rear.

Blessed Sacrament Chapel

This Chapel forms the major part of the 1988-89 additions to the cathedral. The eucharist is reserved in Catholic churches primarily to bring communion to the sick and the dying. By receiving communion, Christ is their strength and the support of the Church is their encouragement. The eucharist is also reserved in a chapel of honour so that the faithful can pray in silence in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament.

The prayer chapel is deliberately modern in style. The tabernacle remains on the principal axis of the building in line with the present and former altars, thus showing the relation of the reservation to the celebration of the eucharist.

Its relationship to the baptismal font is also especially significant. The sacraments of initiation which make a person Christian are three: baptism, confirmation and eucharist. For adults, they are celebrated together at the Easter Vigil. The eucharist is the on-going sacrament of initiation. It is appropriate therefore that the water from the font should provide the context in which the eucharist is reserved.

The sacraments of initiation are symbolised in the magnificent curtain of glass which encloses the apse. The symbols of each sacrament are incorporated into the window (the cross and water of baptism on the right, the flame for confirmation on the left and the cup and bread of the eucharist in the centre behind the tabernacle). The wall is a glass sculpture that captures and transforms light, creating a space that is both uplifting and sublime in its simplicity. The translucence of the space leads the visitor from the confines of cathedral meditation into the life of the city beyond. The window is a major work of internationally-known Sydney artist, Warren Langley.

The tabernacle and monstrance are the work of gold and silversmith, Johannes Kuhman. Intimate in scale and simple in design they are crafted and engraved with crosses in silver and gold. The monstrance, used to display the consecrated bread for veneration, is placed on the tabernacle at times of more intense prayer and adoration.

The front panels of the old Cathedral altar are now located on the opposite side of the wall where the altar once stood. The central image is that of the Emmaus encounter with the risen Christ [Luke 24: 13-35]. Saints Peter and Paul feature to the left and right of the centre panel.

This Chapel forms the major part of the 1988-89 additions to the cathedral. The eucharist is reserved in Catholic churches primarily to bring communion to the sick and the dying. By receiving communion, Christ is their strength and the support of the Church is their encouragement. The eucharist is also reserved in a chapel of honour so that the faithful can pray in silence in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament.

The prayer chapel is deliberately modern in style. The tabernacle remains on the principal axis of the building in line with the present and former altars, thus showing the relation of the reservation to the celebration of the eucharist.

Its relationship to the baptismal font is also especially significant. The sacraments of initiation which make a person Christian are three: baptism, confirmation and eucharist. For adults, they are celebrated together at the Easter Vigil. The eucharist is the on-going sacrament of initiation. It is appropriate therefore that the water from the font should provide the context in which the eucharist is reserved.

The sacraments of initiation are symbolised in the magnificent curtain of glass which encloses the apse. The symbols of each sacrament are incorporated into the window (the cross and water of baptism on the right, the flame for confirmation on the left and the cup and bread of the eucharist in the centre behind the tabernacle). The wall is a glass sculpture that captures and transforms light, creating a space that is both uplifting and sublime in its simplicity. The translucence of the space leads the visitor from the confines of cathedral meditation into the life of the city beyond. The window is a major work of internationally-known Sydney artist, Warren Langley.

The tabernacle and monstrance are the work of gold and silversmith, Johannes Kuhman. Intimate in scale and simple in design they are crafted and engraved with crosses in silver and gold. The monstrance, used to display the consecrated bread for veneration, is placed on the tabernacle at times of more intense prayer and adoration.

The front panels of the old Cathedral altar are now located on the opposite side of the wall where the altar once stood. The central image is that of the Emmaus encounter with the risen Christ [Luke 24: 13-35]. Saints Peter and Paul feature to the left and right of the centre panel.

Reconciliation Chapel

The single chapel of reconciliation incorporates four places for the reconciliation of penitents. The unity of space is maintained by glass panels at floor level and above eye level. The religious quality of the space is enhanced by Warren Langley’s new window and by the screens created by English artist, Michael Brennand-Wood.

It is appropriate that the chapel’s position is closely related to the baptismal font and to the eucharist chapel. Reconciliation leads sinners back to the communion table when they have been estranged from God and the Church. What happened for the first time in Baptism is therefore regularly renewed in this sacrament.

The single chapel of reconciliation incorporates four places for the reconciliation of penitents. The unity of space is maintained by glass panels at floor level and above eye level. The religious quality of the space is enhanced by Warren Langley’s new window and by the screens created by English artist, Michael Brennand-Wood.

It is appropriate that the chapel’s position is closely related to the baptismal font and to the eucharist chapel. Reconciliation leads sinners back to the communion table when they have been estranged from God and the Church. What happened for the first time in Baptism is therefore regularly renewed in this sacrament.

The Baptismal Font

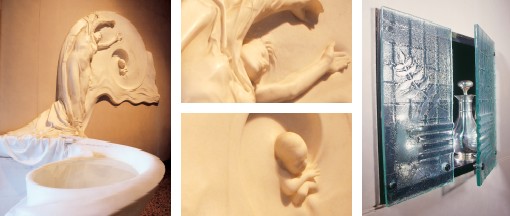

The water in the baptismal font flows from a smaller font where infants will normally be immersed into a lower pool in which adults will kneel as water is poured over them. The water continues in a wide arc which embraces the tabernacle, showing the unity of baptism and eucharist as sacraments of initiation.

One of the most beautiful images used in Christian literature to describe the meaning of baptism is that of the Church as mother who, through the waters of the font, gives birth to a new Christian. This has been stunningly expressed in Carrara marble by sculptor, Peter Schipperheyn. The new-born child symbolises the new Christian emerging from the waters of the font to become part of the family of the Church. The spiral, a form picked up in the font itself, represents the baptismal cycle of death and rebirth. The sculpture is serene and still, sensuous and yet pure; it is classical in its technique, romantic in its emotion and yet undeniably contemporary in its representation of materials – flesh, cloth, water, hair, stone are at times indistinguishable.

Inscribed on the floor near the font is a verse from the 5th century poem of Pope Sixtus III developing the baptismal theme of the church as mother. It comes from the walls of the baptistery of St John Lateran, the cathedral of the city of Rome.

Here a people of godly race are born for heaven; the Spirit gives them life in the fertile waters. The Church-Mother, in these waves, bears her children like virginal fruit she has conceived by the Holy Spirit.

The paschal candle and the holy oils are normally kept near the baptismal font and are used during the celebration of baptism. The paschal candle is the work of silversmith, Hendrik Forster, who also made the sanctuary candelabra. The doors to the holy oils cabinet were made by Warren Langley. The cabinet contains Chrism, Oil of the Sick and Oil of Catechumens.

The water in the baptismal font flows from a smaller font where infants will normally be immersed into a lower pool in which adults will kneel as water is poured over them. The water continues in a wide arc which embraces the tabernacle, showing the unity of baptism and eucharist as sacraments of initiation.

One of the most beautiful images used in Christian literature to describe the meaning of baptism is that of the Church as mother who, through the waters of the font, gives birth to a new Christian. This has been stunningly expressed in Carrara marble by sculptor, Peter Schipperheyn. The new-born child symbolises the new Christian emerging from the waters of the font to become part of the family of the Church. The spiral, a form picked up in the font itself, represents the baptismal cycle of death and rebirth. The sculpture is serene and still, sensuous and yet pure; it is classical in its technique, romantic in its emotion and yet undeniably contemporary in its representation of materials – flesh, cloth, water, hair, stone are at times indistinguishable.

Inscribed on the floor near the font is a verse from the 5th century poem of Pope Sixtus III developing the baptismal theme of the church as mother. It comes from the walls of the baptistery of St John Lateran, the cathedral of the city of Rome.

Here a people of godly race are born for heaven; the Spirit gives them life in the fertile waters. The Church-Mother, in these waves, bears her children like virginal fruit she has conceived by the Holy Spirit.

The paschal candle and the holy oils are normally kept near the baptismal font and are used during the celebration of baptism. The paschal candle is the work of silversmith, Hendrik Forster, who also made the sanctuary candelabra. The doors to the holy oils cabinet were made by Warren Langley. The cabinet contains Chrism, Oil of the Sick and Oil of Catechumens.

Mary, Woman of Faith

The image of Mary, Woman of Faith, shows her standing with hands extended in trust, open to do the will of God. She draws the person who comes to pray into that same response of faith in God’s promises and trust in God’s goodness. Through Mary’s act of faith, God gave Christ to the world; through Mary’s example of faith, we are encouraged to rely on the powerful love of Christ our mediator. We come to the shrine to light a candle, to leave a few flowers, to kneel in prayer so that our trust in God may join Mary’s trust, so that our prayer may become Mary’s prayer, so that our cry in time of need may also be Mary’s intercession.

Other inspiring figures of faith from the scriptures help to create a context for the central image of Mary. The first plaque inside the shrine shows the annunciation of the birth of Isaac to Abraham and Sarah. Despite their advanced age, they trusted when God promised to make their descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky or as the grains of sand by the sea.

The second image shows Naomi and Ruth gleaning in the field of Boaz. Ruth’s faithfulness led to marriage and she became the great-grandmother of David whose descendants include Jesus. A larger relief sculpture illustrates the gospel story of the sick woman in the crowd who reaches out to touch Jesus’ cloak. She was healed and Jesus said to her, “Your faith has restored you to health”.

The Virgin Mary’s own response of faith is portrayed in the panels of the annunciation and the visitation. Finally Mary is shown with the apostles at Pentecost, placing her in the midst of the early Church, sharing its life of faith.

John Elliott has produced a sculpture that the art world already recognises as one of the finest religious works produced in Australia in the final decades of the twentieth century.

The image of Mary, Woman of Faith, shows her standing with hands extended in trust, open to do the will of God. She draws the person who comes to pray into that same response of faith in God’s promises and trust in God’s goodness. Through Mary’s act of faith, God gave Christ to the world; through Mary’s example of faith, we are encouraged to rely on the powerful love of Christ our mediator. We come to the shrine to light a candle, to leave a few flowers, to kneel in prayer so that our trust in God may join Mary’s trust, so that our prayer may become Mary’s prayer, so that our cry in time of need may also be Mary’s intercession.

Other inspiring figures of faith from the scriptures help to create a context for the central image of Mary. The first plaque inside the shrine shows the annunciation of the birth of Isaac to Abraham and Sarah. Despite their advanced age, they trusted when God promised to make their descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky or as the grains of sand by the sea.

The second image shows Naomi and Ruth gleaning in the field of Boaz. Ruth’s faithfulness led to marriage and she became the great-grandmother of David whose descendants include Jesus. A larger relief sculpture illustrates the gospel story of the sick woman in the crowd who reaches out to touch Jesus’ cloak. She was healed and Jesus said to her, “Your faith has restored you to health”.

The Virgin Mary’s own response of faith is portrayed in the panels of the annunciation and the visitation. Finally Mary is shown with the apostles at Pentecost, placing her in the midst of the early Church, sharing its life of faith.

John Elliott has produced a sculpture that the art world already recognises as one of the finest religious works produced in Australia in the final decades of the twentieth century.

Stations of the Cross

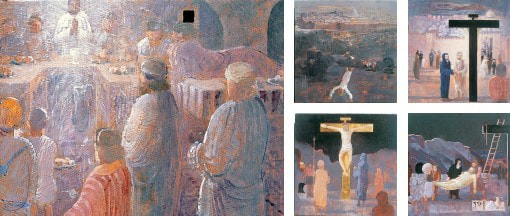

Pilgrims in Jerusalem followed the route taken by Christ as he walked to Calvary. Wishing to reproduce the meditation on Christ’s passion when they returned home, they set up a number of images showing each stage of Christ’s journey. The practice of praying at each station in turn became popular and widespread at the end of the middle ages, though the number and subjects of the stations varied considerably until the beginning of the 19th century.

These Stations were painted by celebrated Australian artist, Lawrence Daws. Their relatively small scale gives them an intimacy which leads to personal contemplation. In planning the paintings, Daws undertook a meticulous study of the life and geography of Jerusalem at the time of Jesus. Each painting is carefully constructed to invite the viewer to step into the deep space created in the picture and to read there the meaning of the event. The gestures, the figures and the objects speak of suffering, redemption and triumph, of injustice and liberation, of conflict, love and compassion.

Pilgrims in Jerusalem followed the route taken by Christ as he walked to Calvary. Wishing to reproduce the meditation on Christ’s passion when they returned home, they set up a number of images showing each stage of Christ’s journey. The practice of praying at each station in turn became popular and widespread at the end of the middle ages, though the number and subjects of the stations varied considerably until the beginning of the 19th century.

These Stations were painted by celebrated Australian artist, Lawrence Daws. Their relatively small scale gives them an intimacy which leads to personal contemplation. In planning the paintings, Daws undertook a meticulous study of the life and geography of Jerusalem at the time of Jesus. Each painting is carefully constructed to invite the viewer to step into the deep space created in the picture and to read there the meaning of the event. The gestures, the figures and the objects speak of suffering, redemption and triumph, of injustice and liberation, of conflict, love and compassion.

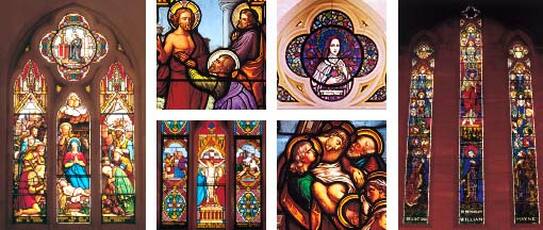

Stained Glass Windows

These outstanding examples of the art of stained glass come from France, Germany, Ireland, England and Australia and make up one of finest collections of 19th century stained glass in Australia. Most of the glass in the nave is from the 1880s while that in the transepts has been made since the 1920s. In 1989, the cathedral was enriched with new glass by Sydney artist, Warren Langley.

The subjects depicted in the windows fall into several groups:

These outstanding examples of the art of stained glass come from France, Germany, Ireland, England and Australia and make up one of finest collections of 19th century stained glass in Australia. Most of the glass in the nave is from the 1880s while that in the transepts has been made since the 1920s. In 1989, the cathedral was enriched with new glass by Sydney artist, Warren Langley.

The subjects depicted in the windows fall into several groups:

- scenes from Jesus’ birth and infancy (including the annunciation to Mary and the visitation) are portrayed a number of times. These are often shown together with other pictures of the Virgin Mary. This group is concentrated in the right (south) aisle and transept.

- the story of Jesus’ suffering and death. They are concentrated in the left (north) aisle and transept. This theme is completed and balanced by images of Jesus’ glorification (the resurrection, the risen Christ and the ascension). The image of the ascension occurs at both ends of the cathedral.

- Jesus’ ministry is represented only by the sermon on the mount and the raising of Lazarus.

- Finally, there is a group of saints who figure in the windows, mainly in the west window and the north transept (Stephen, Peter, Paul, Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, Aloysius Gonzaga, Philomena, Anthony of Padua, Theresa of Lisieux, Margaret Mary).

|

Clarke Window - The East window is one of the finest examples of stained glass in Australia. The work of Harry Clarke of the Dublin firm J. Clarke and sons, it was commissioned by Archbishop Duhig on 10 June 1923. It is inscribed to the memory of Isaac and William Mayne and was given by their brother and sister.

The window shows Christ standing on the clouds as if on a jewelled sea, ascending into heaven over a wonderful sunset. The eleven apostles stand on each side and below stands Mary. In sorrow and desolation they look upward at the departing figure.

|

St Thérèse - Located about the north transept door, the window is the work of Harry Clarke of Dublin. It depicts St Thérèse of Lisieux, the ‘little flower’, a 19th century Carmelite nun. She died at the age of 24 and was canonized in 1925, the same year this window was donated by Mrs Thomas Anderson of Kangaroo Point.

The Shrine of Saint Mary MacKillop

Mary MacKillop was born in Melbourne in 1842 and died in Sydney in 1909. She took the religious name Mary of the Cross. Responding to the isolation of colonial families she pioneered a new form of religious life to provide education for their children. She and her sisters shared the life of the poor and the itinerant, offering special care to destitute women and children. She is remembered for her eagerness to discover God’s will in all things, for her charity in the face of calumny and for her abiding trust in God’s providence.

Mary MacKillop worked in Brisbane after her final profession as a religious, and regularly worshipped in this building between Christmas 1869 and Easter 1871. Soon after she was beatified in 1995 Archbishop John Bathersby announced that a diocesan shrine to Mary MacKillop would be created in old St Stephen’s.

There are, of course, photographs of Mary MacKillop, but a shrine for devotion must do much more than capture a physical likeness. It must lead people into the spirit of the blessed woman and evoke a sense of awe.

Brisbane sculptor, John Elliott, began with the trunk of a hundred-year-old camphor laurel tree. He sliced it and hollowed it out and then began painstakingly to recombine its elements, allowing the figure of Mary MacKillop to emerge. The ancient tree and its rough bark recall the slab hut in which she opened her first school, and the old fence posts she passed as she travelled through the Australian bush on horseback.

The figure of Mary MacKillop evokes the tough pioneering spirit of this holy woman. Her faith and trust in God’s providence is shown in her determination as she strides forward. Yet her face tells of her warmth and compassion for those in need.

The four panels enclosing the shrine are the work of John Elliott. The drawing on the panels pay tribute to Mary’s religious life and her work encouraging the sisters in their ministry – especially by her letter writing. It also allows us to discover children, Australian animals and other elements of her life and ministry.

Mary MacKillop was born in Melbourne in 1842 and died in Sydney in 1909. She took the religious name Mary of the Cross. Responding to the isolation of colonial families she pioneered a new form of religious life to provide education for their children. She and her sisters shared the life of the poor and the itinerant, offering special care to destitute women and children. She is remembered for her eagerness to discover God’s will in all things, for her charity in the face of calumny and for her abiding trust in God’s providence.

Mary MacKillop worked in Brisbane after her final profession as a religious, and regularly worshipped in this building between Christmas 1869 and Easter 1871. Soon after she was beatified in 1995 Archbishop John Bathersby announced that a diocesan shrine to Mary MacKillop would be created in old St Stephen’s.

There are, of course, photographs of Mary MacKillop, but a shrine for devotion must do much more than capture a physical likeness. It must lead people into the spirit of the blessed woman and evoke a sense of awe.

Brisbane sculptor, John Elliott, began with the trunk of a hundred-year-old camphor laurel tree. He sliced it and hollowed it out and then began painstakingly to recombine its elements, allowing the figure of Mary MacKillop to emerge. The ancient tree and its rough bark recall the slab hut in which she opened her first school, and the old fence posts she passed as she travelled through the Australian bush on horseback.

The figure of Mary MacKillop evokes the tough pioneering spirit of this holy woman. Her faith and trust in God’s providence is shown in her determination as she strides forward. Yet her face tells of her warmth and compassion for those in need.

The four panels enclosing the shrine are the work of John Elliott. The drawing on the panels pay tribute to Mary’s religious life and her work encouraging the sisters in their ministry – especially by her letter writing. It also allows us to discover children, Australian animals and other elements of her life and ministry.

Francis Rush Centre Works of Art

The Francis Rush Centre, and its surroundings, includes a number of works of art by artists Rhyl Hinwood, Thomas Justice and Judy Watson. Click here for more information.